It was heartening to see the thoughtful and heartfelt correspondence among Diggers members in recent magazine issues about how wind farms and energy infrastructure affect the natural environment.

It’s beyond doubt that climate change is happening, and with it, a rise in extreme weather events that threaten both human settlement and nature. To stop climate change getting worse, we need to restore the balance between the carbon dioxide going into the atmosphere and the carbon dioxide being taken out, via natural and other processes. This is often shortened to ‘net zero’.

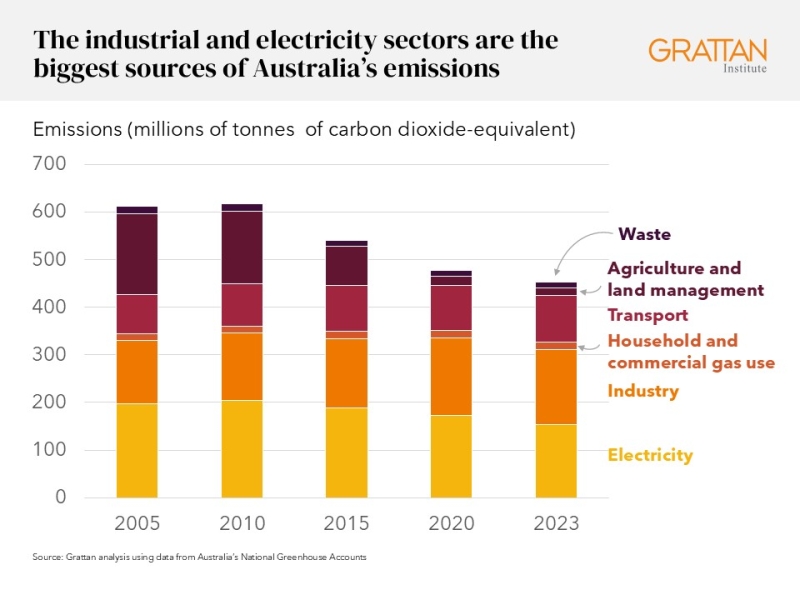

Most of Australia’s emissions come from the electricity and industrial sectors, followed by transport, agriculture and land management practices, as well as waste (Figure 1). The pathway to eliminating most emissions from our economy starts with electricity – replacing coal generators and some gas ones with wind, solar, batteries and other storage. Then we use electricity to replace petrol and diesel in our cars, and to replace a large portion of coal and gas use in industrial facilities.

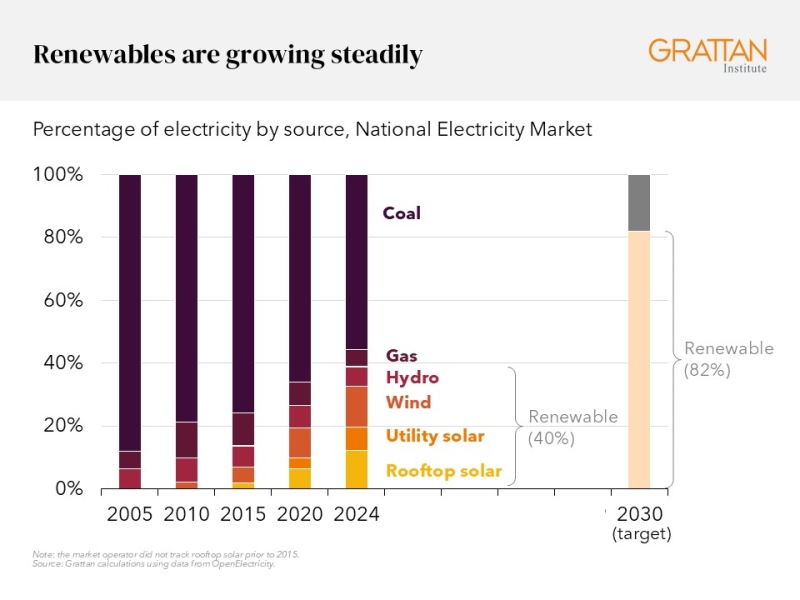

Increasing numbers of wind turbines and solar panels are being installed around the country so that we have access to cleaner electricity. Since 2000, the share of wind, solar and hydroelectricity has grown from about 8% to 40% (Figure 2).

The government has an ambitious target of reaching 82% by 2030. This means building more wind and solar farms, along with transmission lines to connect them to the grid.

Australia actually gets more of its electricity from solar power than from wind (Figure 2). This is in part because of the world-leading popularity of rooftop solar with Australian households. About one in three households now have solar on their roof.

For anything we use – from plastic pots in the garden to household appliances and batteries – we should be concerned about whether it can be recycled at the end of its life.

The Smart Energy Council estimates that currently only about 5% of solar panels are recycled.1 This isn’t creating large amounts of waste at present because not many solar systems are being decommissioned. But it could become a big problem if not addressed. About 95% of the material in a solar panel could potentially be recycled. The solar industry knows this and is working to develop a mandatory national recycling scheme.2

About 90% of the materials from decommissioned wind turbines can be recycled.3 But the blades are often made of fibreglass or composite materials, which aren’t recyclable, and Australia does not currently have plans to stop blade waste going to landfill. But the amount of waste is minuscule compared to total construction and demolition waste.4

Diggers correspondents also discussed sulphur hexafluoride – a potent greenhouse gas that is used in switchgear and substations, primarily for insulating cables and circuit breakers. Sulphur hexafluoride has a global warming potential 23,500 times higher than carbon dioxide. Luckily, we don’t use much of it – about 6 tonnes for the whole of Australia in 2023. This would have warmed the planet as much as 143,430 tonnes of carbon dioxide and was equivalent to 0.03% of national emissions in that year.5

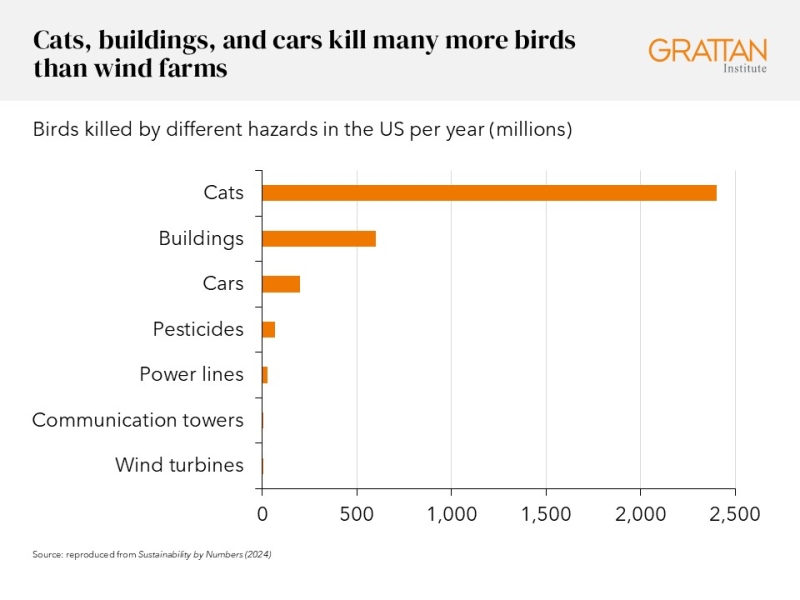

When it comes to impact on bird life, it’s important to know that cats, buildings and cars kill many more birds than wind farms (see US data in Figure 3 – similar data is not available for Australia, but is unlikely to be markedly different).6

But some types of birds are more vulnerable than others. Typically, these are birds that use ridgetops to get a lift from the wind (such as birds of prey) and those that are migratory. And bats are more vulnerable to wind turbines than birds are. Placing turbines away from known habitat and migration paths reduces impact on these species.

There isn’t a zero-impact way to modernise our energy system to make it low-emissions. But we can’t stick with the old system because it is destroying nature by contributing to climate change.

Climate change will profoundly affect all living things, including us. As the creatures with the most agency to prevent the worst effects, we owe it to nature to proceed carefully as we modernise our energy system so that we cause as little harm as possible to the other species we share the planet with.

Alison Reeve is the Program Director of Energy + Climate Change at the Grattan Institute think tank, and has worked on energy and climate policy for 25 years. She gardens enthusiastically but imperfectly in Canberra.

For the Dear Diggers wind farm debate visit www.diggers.com.au/blogs/news/dear-diggers-the-windfarm-debate